Crucial research in understanding medical image perception

Rapid progress in technology and 3D imaging has led to new challenges when interpreting medical images, with two University of Cumbria academics, and their collaborators, recently recognised for their contributions to crucial research in understanding medical image perception.

Associate Professor Tim Donovan and Dr Peter Phillips’s work in helping to establish improved image interpretation has helped inform worldwide guidance from the World Endoscopy Organisation and the American Association of Physicists in Medicine.

The two investigated eye tracking for medical imaging on 2D and 3D datasets to improve our understanding of how practitioners carry out visual searches and make decisions, as well as the occurrence and frequency of errors. Rapid advances in imaging technology and its increased use, require us to know more about its role in decision making in clinical practice.

The findings from this research have also directly benefitted University of Cumbria radiography students, who are acquiring vital new skills in interpreting imaging data.

But what exactly is eye tracking and how has it made a difference to the frequency of radiological errors which have remained unchanged for 60 years?

Dr. Donovan, who works in medical image perception and cognition at the university’s Institute of Health, explained the procedure allowed measurement of eye movement with an infra-red illuminator and high-resolution camera, leading to an increased understanding of radiological performance.

He said: “We are constantly moving our eyes, up to five times a second, to scan the world around us and focus attention on the most relevant part of a scene. Eye tracking tells us where people look, what information is being processed – and for how long.

“This gives an invaluable insight into visual and cognitive processing and as a research tool has provided an understanding of why radiologists make mistakes. These are typically at the rate of three to five percent, but can be up to 30 percent when looking at cross-sectional scans such as MRI and CT.”

Medical images such as x-rays have always had a degree of ambiguity and this key research looked at typical search patterns in a bid to understand and reduce inaccuracies and potentially improve professional training.

The assumption that a radiologist should be able to ‘eyeball’ an image and make an informed decision based on instinct and experience was challenged by this study. It showed where radiologists and radiographers had actually looked at the image and generated data that could improve diagnostics and reduce errors.

Whilst there is some concern that using artificial intelligence could displace radiologists, the counter argument is that computer-aided detection will, in fact, enhance their role.

“This is about small incremental advances in our understanding of how visual expertise is applied to radiology and has become even more relevant now that computer algorithms are used in many tasks,” explained Dr. Donovan.

“However, people will ultimately always need to be involved when decisions are made about medical diagnoses.”

Improving the accuracy of radiology interpretation means that a higher percentage of conditions can be spotted early. An important element of the research has been the imaging diagnosis of colorectal cancer and polyp detection.

Although revealed in CT colonography scans, polyps are often ignored because they can be unclear or hard to spot. However, it was this sort of decision making that had to be improved, concluded the researchers.

Dr. Peter Phillips is a senior lecturer in medical imaging. He is currently working with Dr. Yan Chen, Associate Professor in cancer screening at Nottingham University, while Dr. Donovan continues his collaboration with Dr. Damien Litchfield, of Edge Hill University, on components of visual search.

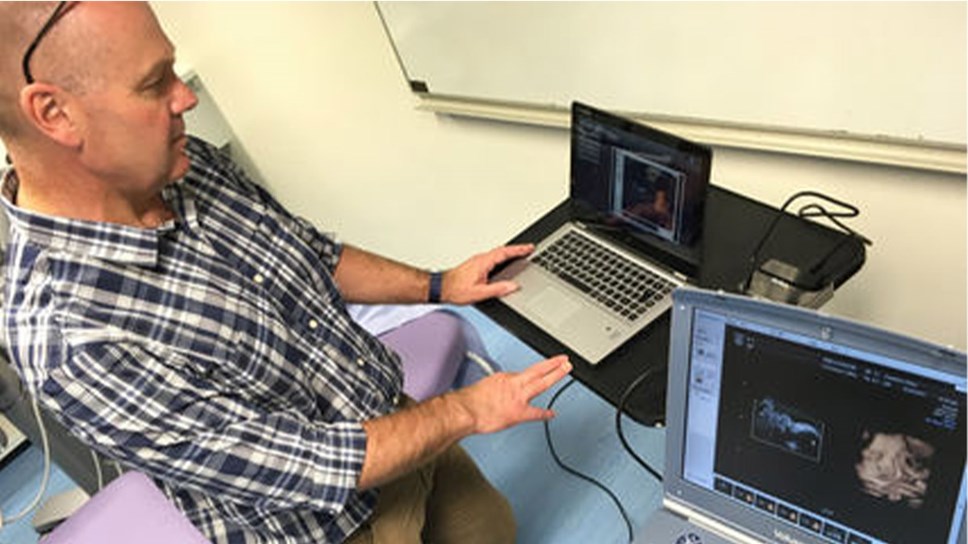

No stranger to renowned research, Dr. Donovan, in collaboration with Prof. Vincent Reid, of Waikato University, New Zealand, and Dr. Kirsty Dunn, Lancaster University, has undertaken research at the university’s ultrasound lab and Blackpool Victoria Hospital, examining the visual perception of babies in the womb - listed as one of 2017’s most important discoveries.

The research used a light source to project a pattern of three dots in the shape of eyes and a mouth through the uterine wall. Measuring the way, the foetus responded using 4D ultrasound, it was found that at 34 weeks they were like new-born babies in preferring face-like stimuli.

Discovery Magazine included the project in the publication’s list of 100 discoveries made that year.